The Yin and Yang of Software Development

Explore the balance between software quality, startup agility, and product development

Published

- 8 min read

What Is Software Development All About?

Depending on who you ask, even if you ask professionals with many years of experience in the industry, you’ll get very different answers. In my experience, there are two clear trends:

-

Software Development is a craft. Your job as a software developer is similar in many ways to that of a gardener. You don’t have a big plan because you don’t need one. You start small, you’re alone, and you build things along the way. If you’re a good gardener, however, you’ll work cleanly and pay attention to the tricky parts of your garden because you know that unless you keep them under control, they’ll soon get out of hand.

-

Software Development is an Engineering discipline. Now, there’s a plan. You have one or more teams, and you’re building something big and complex for which there are clear requirements and constraints. There’s a need for a well-defined architecture, as well as processes that ensure quality requirements. Agile methodologies might let you delay part of the decision-making, but you cannot sacrifice quality.

You might call it the Yin and Yang of Software Development. I believe that both statements are true to some extent, but one may dominate the other depending on the context.

There’s almost always some craft or even some art in the process of software development. When you’re writing code, more often than not, you’re not following a scientifically rigorous method. Instead, you rely on pre-existing components and your experience to build things that work. If you need metrics, these usually come after you’ve already built something. However, depending on the context, you may need to apply engineering processes and quality standards that resemble those used in other engineering disciplines.

These two definitions raise two important questions:

- In which context does one definition rule over the other?

- What is quality in software?

Business Is the Context

When you build software in the context of a startup that is creating a new product from scratch, there are usually so many unknowns about the final product that it often makes little sense to apply most software quality measures.

If you follow Design Thinking, Lean, and Agile principles, you’ll continuously perform experiments and collect data to test your hypotheses. This way, in each iteration, you gain more insights about the right direction for your product.

Typically, during the initial iterations, you’ll have a pretty small team (maybe just one developer), and the advantages of applying software quality principles might not be immediately clear because, often, the code you’re writing won’t live long enough to justify the effort.

As Johnny Schneider explains in Understanding Design Thinking, Lean, and Agile:

[…] Much of this experimentation might not involve writing a line of code—after all, working software is still an experiment, just a really expensive one. As confidence increases and software becomes the experiment, Agile helps teams constantly adapt to change, repeatedly adjusting their course and taking the next steps.

Therefore, during the initial phases of a startup, you should spend your time experimenting and collecting data to make well-informed decisions. This could be interpreted as a technical variant of Paul Graham’s “Do things that don’t scale”. What’s the point of writing a high-quality, scalable solution if you end up throwing it all away?

Some developers might be horrified at the thought of developing software this way. That’s because they don’t see software development as a craft or an engineering discipline, but as a religion. Good developers understand the value of software quality techniques, but they can also see the big picture and recognize the cost of non-functional requirements, especially in the beginning. If you fail to see this, you may end up with an over-engineered solution that is difficult to maintain and poorly addresses the business needs.

The problem with this context, however, is that it changes over time. You may have started out with a bunch of experiments, but at some point, if enough of these experiments succeed, you’ll find yourself offering a real service to real customers.

A good CTO in a startup will constantly try to answer the question: “How much technical debt can we afford?” In the beginning, speed is prioritized over anything else because you cannot afford to spend too much time trying out experiments. Otherwise, you’ll run out of time and resources, and your competition will outpace you before you’ve even started.

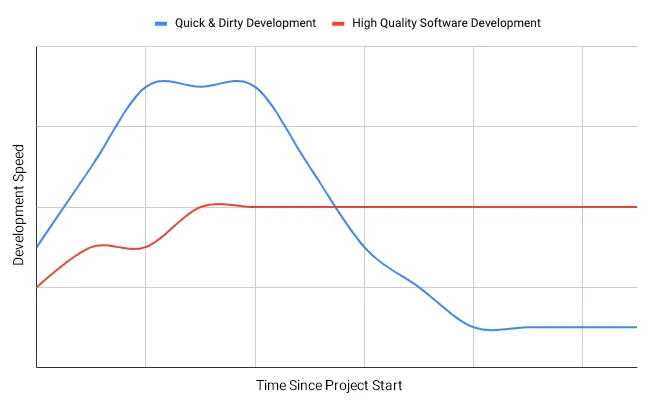

But there’s an inflection point where the velocity (the development speed of new features) will dramatically decrease unless you improve the quality of your software. It’s difficult to tell exactly when this inflection point occurs for a given product, but some indicators are:

- Your codebase is growing rapidly and more people start working on it.

- You start spending more time than usual fixing bugs.

- New developers find it increasingly difficult to become productive.

- You need more time to manually test your product with each release.

- Your customers start complaining about the quality of the service.

The team and its stakeholders should recognize that the insane speed of the initial phases is not sustainable over time. At some point, enough resources should be spent to continuously refactor the codebase before it’s too late. If the goal is to achieve the highest development speed possible, there’s a moment when software quality principles stop being an obstacle and become a crucial part of a virtuous circle where you build better software, faster. In other words, if you don’t care about the quality of your software soon enough, it’s only a matter of time before it becomes unmaintainable, and that will slow you down.

Product Development Stages

During product development, it’s common to use the following terms:

- PoC (Proof of Concept): This is the minimal solution to see if an idea is even feasible. It’s the cheapest way to test a hypothesis.

- Prototype: This is a piece of working software that solves a specific problem. It may have a beautiful design and appear robust, but it doesn’t follow most software development best practices and quality standards. It’s a good way to test a hypothesis, but it’s not maintainable in the long term. Some authors use the term “walking skeleton” for this.

- MVP (Minimum Viable Product): This is a product built on a solid technical base that offers the minimum set of desired features. The goal of an MVP is to hit the market as soon as possible while having a solid starting point that is maintainable in the long term.

After the MVP phase, you may want to continue iterating into a Minimum Marketable Product, a Minimum Lovable Product, or a Minimum Delightful Product…

In my personal experience, most problems during product development arise from misunderstandings about where you are with your product both technically and from a business perspective. It’s the responsibility of the team members to communicate where you stand at any given moment and understand what it means.

Quality Software

I won’t describe in depth what software quality is all about. There’s an article on Wikipedia that defines it pretty well.

In a nutshell, in the context of a startup, quality software means:

- Following best practices:

- From code style guides to DRY, KISS, SOLID principles, etc.

- Continuously refactoring your code.

- Automatically analyzing the complexity of your code.

- Writing tests:

- Not just unit tests, but all kinds of tests. Tests help you keep your solution stable and maintainable. Read the practical test pyramid for more information on it.

- Without tests, the chances of new features breaking existing ones without you realizing it increase exponentially.

- Tests also serve as documentation for new team members.

- Doing code reviews.

- Using continuous delivery pipelines.

- Designing a scalable architecture.

- Monitoring your systems to identify failures and bottlenecks.

Doing this takes time, but it’s an investment. I wouldn’t recommend doing it all while the chances are high that you’ll end up throwing away most of your code. However, as time goes by, you should invest more and more in these practices if you don’t want to end up with a spaghetti code salad that nobody wants to work with.

The later you start applying these principles, the more difficult (and expensive) it becomes to apply them successfully.

Some Final Words

Maybe you’ve always worked in an environment where quality software is valued, which is why you’re probably almost religious when it comes to writing software with high-quality standards. Hopefully, you now see that there are cases where it’s actually better to go the quick & dirty route for a while and activate the feature factory mode.

Feature factories and quick & dirty approaches have a price, though, and I hope that’s clearer now. It’s tempting to try to extend that unnatural velocity peak as much as you can, but you’re playing with fire. I’ve seen countless companies follow that path, only to end up with buggy software and developer scarcity because no one wants to work with such a codebase under such conditions.

If you’re in a team that doesn’t understand that what worked yesterday won’t work today anymore, I’d suggest avoiding quick & dirty altogether.

Then there’s the ghost of a big rewrite. I would avoid rewriting unless it’s strictly necessary because it’s insanely expensive. If you extend the quick & dirty phase for too long, however, sooner or later, there’ll be no other choice.

Back to the top ↑