The Long Game of Building Companies That Stay Relevant

Why a sustainable engineering culture—not just speed—keeps companies innovative, competitive, and relevant.

Some years ago, I read about a concept that stayed with me, though I can’t remember exactly where it came from. It contrasted the Western tendency to pursue rapid wealth with an East Asian perspective that treats companies as living systems—organisms that must be nurtured over time rather than exploited for quick gains. If anyone recognizes the source, I’d love to know.

According to this idea, a new company resembles a child. During its first year, it needs constant care and protection. At five, it begins to walk on its own but still stumbles often. At fifteen, it becomes a teenager—full of potential but prone to mistakes. Only after a few decades does it mature into an adult, capable of giving back to the society that nurtured it. And when it’s nurtured with patience and vision, it doesn’t just make its founders wealthy—it creates prosperity that lasts. A company grown this way leaves behind a legacy, one that can sustain families and communities for generations.

Day 1, Learning, and Maturity

That image has stayed with me, especially when thinking about modern tech companies. It might seem at odds with Amazon’s famous “Day 1” philosophy, but I actually see it as very compatible. Day 1 thinking is about maintaining a sense of curiosity, openness, and willingness to reinvent oneself—qualities that individuals can also carry throughout their entire lives. A person can stay in Day 1 by continuously learning, questioning, and adapting without losing direction or stability. The same is true for companies.

In this sense, the Day 1 mindset is closely related to the concept of the learning organization, described by Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline. Both ideas share a belief that growth and longevity depend on constant learning, feedback, and self-renewal. A learning organization doesn’t stand still; it listens to its environment, experiments, and integrates new knowledge into its identity. That ability to learn continuously is what keeps an organization alive.

A company that matures like an organism doesn’t abandon its Day 1 spirit; it evolves it. Just as adults can’t live by the routines of childhood, mature organizations can’t rely on the same structures, rituals, or processes that worked during their early years. Growth demands change. The goal isn’t to cling to youth or speed for its own sake, but to cultivate an enduring mindset—one that blends the curiosity of Day 1 with the wisdom, discipline, and resilience of adulthood.

Evolving to Stay Relevant

Many of the most enduring tech companies have demonstrated this ability to evolve. Microsoft, for instance, transformed itself from a closed, Windows-centric software vendor into a cloud-first, open-source-friendly company under Satya Nadella’s leadership—embracing Linux, GitHub, and developer ecosystems it once resisted. Apple, once focused solely on personal computers, reinvented itself through design-led consumer electronics and an integrated services ecosystem. IBM, often dismissed as a relic of the mainframe era, has continuously reinvented itself—first around consulting, then cloud and AI—demonstrating that adaptability and relevance are not confined to startups.

These transformations show that staying in Day 1 doesn’t mean staying small or scrappy—it means being willing to rethink core assumptions. True maturity isn’t the start of Day 2; it’s the ability to evolve structures and beliefs as context changes, supported by a culture that learns as it grows.

The Structural Maturity Challenge in Software Organizations

“When teams are forced to operate like internal contractors, they spend energy proving their worth instead of building enduring value”

In the world of software, many companies hit a growth barrier that’s not technical but structural. Early success often comes from agility and improvisation, but those same qualities can become liabilities when the organization scales. A startup can get away with a few shortcuts—an undocumented process here, a manual deployment there—but as the product portfolio expands and complexity increases, those habits start to show their cost.

To continue delivering high-quality products, the company must evolve its internal structures. It needs stable platforms, shared practices, and roles that look beyond immediate deadlines. Strategic investments in developer experience, architecture, and cross-functional coordination are no longer optional—they become prerequisites for reliability and innovation.

Many organizations struggle here because they still operate under a consulting mindset: each project or feature must have a sponsor, a scope, and a business case that justifies the team’s time. That approach can sustain a small firm that delivers software for others, but it works against a company that develops its own products. Product organizations thrive on long-term vision and continuous improvement, not on the transactional logic of billable hours. Studies show that product-led organizations investing in persistent, cross-functional teams achieve faster innovation cycles and higher customer satisfaction than project-funded setups (McKinsey’s “The Big Product and Platform Shift” and “The Impact of Agility” further reinforce these findings). Companies such as Spotify and Netflix also illustrate this principle in practice, maintaining enduring teams that evolve products continuously instead of resetting priorities with every project.

When teams are forced to operate like internal contractors, they spend energy proving their worth instead of building enduring value. Engineers, designers, and product managers become trapped in short-term output cycles with no time to invest in the foundations that make sustainable software possible. This is where the cracks start to appear—and where the idea of toil becomes painfully relevant.

Toil and the Square Wheel

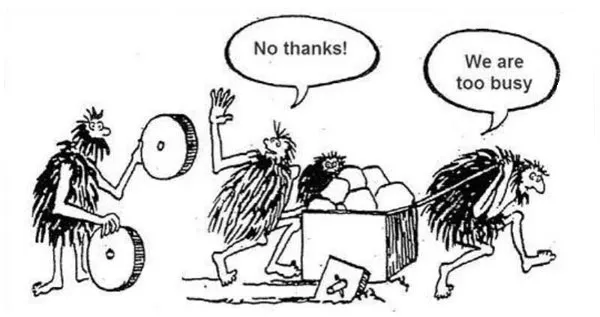

In Site Reliability Engineering (SRE), there’s a rule: teams should never spend all their time on toil—manual, repetitive work that keeps the system running but produces no improvement. If they do, innovation dies. And when innovation dies, it’s not just that we stop releasing new and exciting features; we begin wasting time and energy maintaining inefficient processes that could have been automated or improved. Over time, the team’s creativity and problem-solving capacity shrink under the weight of operational tasks that add no long-term value.

The same principle applies to organizations. When every hour must be spent on something billable or directly linked to a feature, there’s no room to step back and improve how we work. It means less time for process refinement, automation, tooling, and cross-team alignment—the activities that reduce friction and free up space for genuine innovation. Without deliberate investment in improvement, teams find themselves trapped in a cycle of firefighting and manual maintenance. We end up, as in the famous meme, pushing a cart with square wheels because “we don’t have time to try round ones.”

Building Roots, Not Just Branches

In mature software companies, there’s an understanding that not all work produces an immediate payoff—but some work multiplies everything else. That’s why they invest in roles like Developer Relations, Platform Engineering, Developer Experience, or internal education.

These teams don’t build customer-facing features; they build the roots that make every branch stronger. Their work ensures that engineering principles, tooling, and culture are consistent and scalable across locations. In global organizations, this is what allows engineers in different countries and time zones to speak the same technical language, share the same practices, and evolve those practices together. A strong engineering culture doesn’t emerge by chance—it’s cultivated intentionally through shared platforms, reusable systems, and communities of practice that connect people beyond their immediate teams.

Without these roles, each location becomes an isolated island—each building its own pipeline, design system, or process for lack of shared infrastructure and communication. Over time, this fragmentation leads to duplicated effort, inconsistent quality, and a diluted sense of identity. By contrast, when a company invests in the connective tissue that unites its engineering culture, it not only becomes more efficient but also more cohesive. Developers feel part of something bigger, contributing to a common craft rather than a local workaround.

A Call for Long-Term Thinking

If we treat software organizations as living systems, then it’s clear they need more than budgets and KPIs. They need care, patience, and a shared sense of purpose.

A child doesn’t grow stronger by being rushed; it grows by being nurtured. The same goes for our companies. We can’t expect innovation if we don’t create the conditions for it to emerge. As described in Accelerate by Nicole Forsgren et al., innovation and performance are not by-products of luck but of deliberate cultural design. High-performing organizations remove friction continuously, automate relentlessly, and measure success by how quickly ideas move from concept to customer.

One of the most influential frameworks cited in that book, Westrum’s model of organizational culture, distinguishes between pathological, bureaucratic, and generative cultures. Generative cultures—those that value learning, information flow, and mutual trust—are proven to correlate directly with speed, quality, and reliability. In such environments, teams can share knowledge, admit failure, and recover faster, creating a virtuous cycle of improvement.

For many Western companies, achieving that generative state requires rethinking regulation and governance. Excessive rigidity—whether from corporate bureaucracy or external compliance requirements—creates a form of organizational toil. It slows down feedback loops and makes improvement difficult. If we Europeans want to remain competitive against younger and more adaptive companies emerging from Asia and America, we must foster cultures that prioritize learning, experimentation, and a relentless focus on removing obstacles that slow us down.

Somewhere between the chaos of the startup phase and the bureaucracy of the corporate world lies a fragile balance: an organization that values enablement over control, autonomy over silos, and craft over speed. It’s not about centralization. It’s about maturity—a form of maturity that continuously questions itself, learns from its mistakes, and adapts without losing its purpose.

Focus Under Constraints

Sometimes, the challenge isn’t just structural—it’s financial. When budgets tighten, it might be tempting to cut back on the very cultural and structural investments that keep an organization healthy. But doing more with less doesn’t mean spreading teams thinner; it means focusing sharper. When resources are limited, clarity and focus become your most powerful multipliers.

A reduced budget forces choices, and those choices should sharpen—not erode—your company’s purpose. Instead of maintaining a sprawling portfolio of products, it’s often wiser to concentrate on fewer initiatives that can truly excel. When Steve Jobs returned to Apple after NeXT, one of his first moves was to slash the company’s product line from dozens of confusing variants to just four clear bets. That focus didn’t shrink Apple—it made it great. Every engineer, designer, and product manager knew where to direct their energy, and excellence followed.

The same principle applies to software organizations under pressure: don’t sacrifice your culture, your learning, or your commitment to quality. Instead, narrow your scope and raise your standards. Focused teams with a strong shared purpose can achieve remarkable things even in lean times, because they spend their time building what truly matters.

Closing Thoughts

If there’s one idea that ties all this together, it’s that building great companies is an act of patience and intention. Maturity doesn’t mean slowing down—it means learning to direct energy where it compounds. Companies that invest in their foundations, in learning, and in removing friction create the conditions for long-term innovation, competitiveness, and continued relevance.

The challenge for modern organizations, especially in today’s Europe, is to combine speed with reflection: to evolve structures without losing curiosity, and to keep improving while remaining unafraid to discard what no longer works. The best companies embrace a beginner’s mindset—ready to question established norms, rebuild processes when needed, and constantly look for better ways to operate. They grow deliberately—continuously learning, pruning what no longer serves them, and cultivating the systems and culture that allow them to thrive for decades, not just quarters.

Back to the top ↑